Did you know that when, and how much, protein you consume impacts your overall metabolism and satiety levels throughout the entire day? Consuming a high-protein breakfast, anywhere from 20 g to 39 g protein [1], enhances satiety and reduces subsequent energy intake.

Although overall dietary protein consumption in the US is adequate based on current recommendations, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that the majority of protein is consumed at dinner [2], while protein consumed at breakfast is well below the levels shown to favorably affect appetite and metabolism [3]. In fact, approximately 20% of US men and women consume absolutely nothing for breakfast [4].

Benefits of Breakfast [5]

- Provides energy for the brain.

- Provides nutrients to meet the daily requirements.

- Reduces risk of overweight and obesity.

Benefits of High Protein Breakfast

- Improves short-term appetite control and satiety.

- Reduces subsequent energy intake over a 24-hour period, particularly of high fat, evening snacks [6], and lunchtime meals [7-11].

- Reduces postprandial glycemic response and insulinemic responses [1].

Recommendations

- The greatest effects of a high-protein breakfast are seen in protein intakes > 20 g, and most consistently at intakes > 30 g per meal. As an example, two eggs and one 6-ounce plain, nonfat, Greek yogurt consist of 22 g protein in totality.

a. Aside from eggs and Greek yogurt, other sources of protein include:

- Peanut butter

- Quinoa porridge

- Sliced avocado

- Low fat cottage cheese

- Protein smoothies.

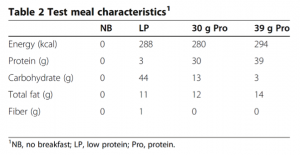

It is important to evenly distribute your consumption of protein throughout the entire day. With that being said, approximately of your daily protein should be consumed at breakfast. The research of Rains et al. [1], published in the Nutrition Journal, conducted a randomized, controlled, crossover study, to determine the effects of high-protein breakfast consumption on appetite, postprandial glycemic and insulinemic responses, and caloric intake at lunchtime. 34 normal weight to overweight (BMI 18.5 to 29.9 ), premenopausal women (ages 18-55 y), who were regular consumers of breakfast and lunch, were randomly assigned to consume a high-protein (30 or 39 g) sausage and egg-based frozen convenience meal, a low-protein (3 g) meal consisting of pancakes and syrup, or to not consume a meal of any kind. The table below (Rains et al., 2015), illustrates the characteristics of all four test meals.

Results of Rains et al. (2015)

- Improved appetite control, reduced postprandial glycemic and insulinemic responses, and lower energy intake at lunchtime, is greatest when consuming a high-protein (30 g and 39 g) breakfast.

- There were minimal differences in responses between the two protein-containing meals, suggesting that both protein levels (30 g and 39 g) were sufficient.

Conclusions and Practical Implications

- Convenient, high-protein, breakfast options, would be potentially beneficial for individuals interested in reducing morning hunger and energy intake later in the day as well as glycemic excursions.

- Such meals are easy to prepare, compared to other high-protein foods consumed at breakfast, which require a greater degree of preparation.

- Increased satiation, and therefore better adherence to caloric restriction, is one potential mechanism by which high protein diets may facilitate weight loss.

Other Research Findings

- Even adolescents, who habitually skip breakfast, have shown an improved short-term appetite control and satiety when consuming high-protein breakfasts [12-14].

- Several meta-analyses from long-term, higher protein, weight loss and/or weight maintenance diets report reduction in glycated hemoglobin and/or fasting insulin concentrations with higher versus normal protein diet [15-16].

- High protein meals have been shown to decrease levels of the hunger stimulating hormone ghrelin and/or promote the increase in the satiety stimulating hormones peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1, resulting in increased perceptions of satiety [17, 9, 18-20].

References

- Rains TM, Leidy HJ, Sanoshy KD, Lawless AL, Maki KC. A randomized, controlled, crossover trial to assess the acute appetitive and metabolic effects of sausage and egg-based convenience breakfast meals in overweight premenopausal women. Nutr J. 2015;14:17

- Fulgoni 3rd VL. Current protein intake in America: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1554S–7.

- Rains TM, Maki KC, Fulgoni 3rd VL, Auestad N. Protein intake at breakfast is associated with reduced energy intake at lunch: an analysis of NHANES 2003–2006. FASEB J. 2013;27:349.7.

- Kant AK, Graubard BI. Secular trends in patterns of self-reported food consumption of adult Americans: NHANES 1971–1975 to NHANES 1999–2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1215–23.

- Blondin SA, Anzman-Frasca S, Djang HC, Economos CD. Breakfast consumption and adiposity among children and adolescents: an updated review of the literature. Ped Obes. 2016;11:333-348.

- Leidy HJ, Ortinau LC, Douglas SM, Hoertel HA. Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese, “breakfast-skipping”, late-adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:677–88.

- Fallaize R, Wilson L, Gray J, Morgan LM, Griffin BA. Variation in the effects of three different breakfast meals on subjective satiety and subsequent intake of energy at lunch and evening meal. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:1353–9.

- Vander Wal JS, Marth JM, Khosla P, Jen KL, Dhurandhar NV. Short-term effect of eggs on satiety in overweight and obese subjects. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24:510–5.

- Leidy HJ, Racki EM. The addition of a protein-rich breakfast and its effects on acute appetite control and food intake in ‘breakfast-skipping’ adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34:1125–33.

- Ratliff J, Leite JO, de Ogburn R, Puglisi MJ, VanHeest J, Fernandez ML. Consuming eggs for breakfast influences plasma glucose and ghrelin, while reducing energy intake during the next 24 hours in adult men. Nutr Res. 2010;30:96–103.

- Clegg M, Shafat A. Energy and macronutrient composition of breakfast affect gastric emptying of lunch and subsequent food intake, satiety and satiation. Appetite. 2010;54:517–23.

- Karatsoreos IN, Thaler JP, Borgland SL, Champagne FA, Hurd YL, Hill MN. Food for thought: hormonal, experiential, and neural influences on feeding and obesity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:17610–6.

- Probst A, Humpeler S, Heinzl H, Blasche G, Ekmekcioglu C. Short-term effect of macronutrient composition and glycemic index of a yoghurt breakfast on satiety and mood in healthy young men. Forsch Komplementmed. 2012;19:247–51.

- Bertenshaw EJ, Lluch A, Yeomans MR. Satiating effects of protein but not carbohydrate consumed in a between-meal beverage context. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:427–36.

- Johnstone AM, Stubbs RJ, Harbron CG. Effect of overfeeding macronutrients on day-to-day food intake in man. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:418–30.

- Clifton PM, Condo D, Keogh JB. Long term weight maintenance after advice to consume low carbohydrate, higher protein diets–a systematic review and meta analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:224–35.

- Leidy HJ, Carnell NS, Mattes RD, Campbell WW. Higher protein intake preserves lean mass and satiety with weight loss in pre-obese and obese women. Obesity. 2007;15:421–9.

- Belza A, Ritz C, Sorensen MQ, Holst JJ, Rehfeld JF, Astrup A. Contribution of gastroenteropancreatic appetite hormones to protein-induced satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:980–9.

- Batterham RL, Heffron H, Kapoor S, Chivers JE, Chandarana K, Herzog H, et al. Critical role for peptide YY in protein-mediated satiation and body-weight regulation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:223–33.

- Blom WA, Lluch A, Stafleu A, Vinoy S, Holst JJ, Schaafsma G, et al. Effect of a high-protein breakfast on the postprandial ghrelin response. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:211–20.

Written by Nicole Lindel ~ Nutrition Education Master’s Student at Columbia University